Joan Fry — a writer's life

This travelog originally appeared in the Belize Forums

The first time I set foot in British Honduras, as Belize was called in 1962, I was twenty years old and newly married to an anthropologist. The airport in Belize (now Belize City), was next to a dirt road in a clearing in the rainforest.

The customs official went through our suitcases item by item, stopping to exclaim over our belongings—Terry’s binoculars and laced boots, my typewriter. He seemed particularly taken by my flower-printed bras and underpants. As I felt my face turn red with embarrassment, he held them up so his co-workers could marvel too.

In Belize City Terry and I stayed at a small guest house, where we slept under mosquito netting and showered in a tiny room under the cistern that had rock walls and an open drain in the floor. The bath water, like the sewage from the toilet, ran directly under the house into a canal. The city was criss-crossed with them, and they all emptied directly into the Caribbean. Some of the stones in the shower were covered with luxuriant black moss, so shiny they glistened. One day while I was washing my hair, some of my shampoo landed on a moss-covered rock, and it flinched. They weren’t rocks at all. They were tarantulas. I didn’t wash my hair again until we reached Don Owen-Lewis’s house in Machaca Creek.

In those days the only way to get to Toledo District was by boat—there were no roads. The Heron H. hauled cargo, the mail, and passengers to points south, all the way to Puerto Barrios in Guatemala. Then she turned around and headed back up the coast. We were only three or four hours south of Belize City when the tail end of a hurricane slammed us. I spent a miserable, seasick night in my bunk, too apathetic to slap at the cockroaches that swarmed over my bare legs. Terry had paid extra for a cabin, but all it had in it were two stained, naked mattresses—no pillows, no sheets, no mosquito netting, no nothing.

In spite of the rough seas, the Heron stopped several times during the night to pick up passengers. Hurricane Hattie had destroyed a lot of the country the previous year, including the wharf at Monkey River Town (now Dangriga). While the Heron pitched and wallowed, people squatted on pilings—all that was left of the wharf—and handed children and packages to people already on board. In spite of my lethargy, I was surprised that nobody got swept off the pilings and drowned.

By the time Terry and I staggered ashore in Punta Gorda, I had only one desire in life: I wanted the ground to stop moving. Don met us in his four-wheel drive Toyota and drove us to his house over a one-lane dirt road with the occasional “passing bay,” a space where a driver could pull off to accommodate a driver coming from the opposite direction. (I don’t think we ever encountered another driver. Most people rode bicycles.) Don was a Brit—his official title was Amerindian Development Officer. He was funny and irreverent and I liked him immediately. For the next week he made sure we were properly bathed (his house had a real shower) and entertained, and that his housekeeper kept bowls of fresh fruits in front of us at all times.

When Don judged us fit to travel, he drove us and all our belongings to San Antonio and dropped us off at the Catholic church. The Jesuit priest there was so desperate for teachers that he’d signed me up, sight unseen, to teach in Santa Elena, even though I wasn’t Catholic and had no previous teaching experience.

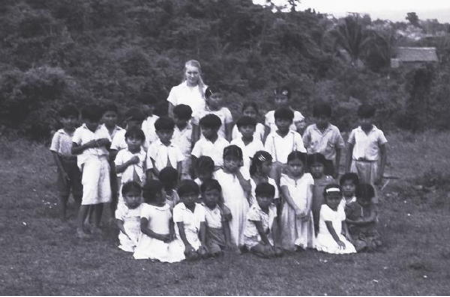

Terry and I moved into our new house—my first home as a newlywed—in August, 1962. While I taught the 3 Rs to every child in the village between the ages of five and fourteen, Terry studied the Kekchi Maya. He was the first American anthropologist to do so, and I was the first white woman most of the Maya had ever seen. I lived in that house—a bush house, just like theirs, with a thatched roof, plank walls, doors made out of saplings tied together with vines, and a dirt floor—and cooked over an open fire for the next ten months. I was living there when I turned twenty one.

Fast forward to June, 2005. The Belize City International Airport looks completely different—bigger, for one thing, and it consists of more than one large room. This time nobody is remotely interested in my underwear. The immigration official notices that my final destination is Punta Gorda. Unlike the Cayes and spectacular Maya ruins in the north, Toledo District has yet to become a tourist attraction.

“You been to PG before?” he asks.

“Forty-two years ago,” I tell him. “This is the first time I’ve been back.”

His eyes widen. He looks barely thirty—he could be my son. A slow grin crosses his face. “It going be different.”

I grin back. Yup. The question is, how different?

I have my answer when I arrive in Punta Gorda: so different I might have lived in an entirely different country than the one I’m looking at now. PG is still a Garifuna town, and the people are still laid back and very friendly. To my surprise there’s more than one street—and they’re all paved. The houses used to be unpainted wood, silver from the salt water, and they stood on stilts, so the rising sea during hurricanes would flow under them instead of carrying them out to sea. Now PG resembles any small coastal town in the Caribbean.

Don and his daughter Francisca, who was born the year after I left, and three of his grandchildren are at the airport to greet me. Don is seventy-nine now, his hair white as dandelion fluff. But I would have recognized him as soon as he opened his mouth. His sense of humor hasn’t changed, and his Limey accent is as strong as ever. I would have been back earlier, but I thought Don was dead—until a complete stranger on the Belize Forums set me straight.

In spite of a drought so severe that the rivers are drying up, the countryside is still green, the cloudless sky the same brilliant blue I remember. But what strikes me at once is the bush. It was a great deal higher and more lush when I last saw it, and empty. Now houses and little farms dot the landscape and the bush is little more than scrub.

I arrive just in time to eat dinner with the archaeological team spending the summer at Don’s. Their base camp is behind his house in a separate building.

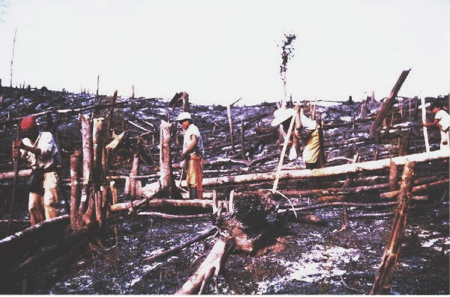

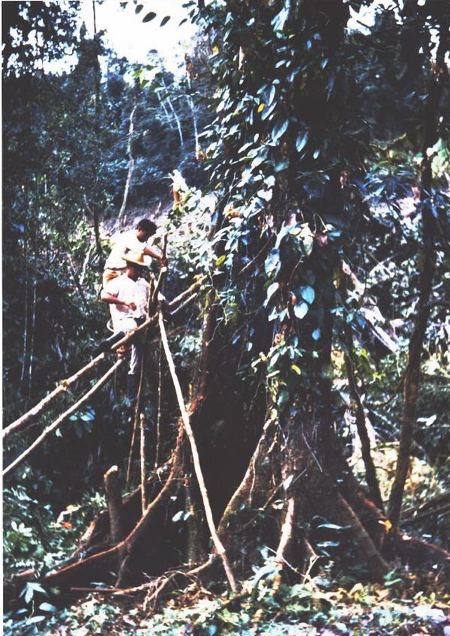

After dinner I take out copies I made of my old photos. Most are of Don and his family; the rest are of my former students and neighbors in Santa Elena. The ones that interest the archaeologists are color prints of the Kekchi cutting bush to make new milpas (cornfields). The head of the project takes a long look at one photo in particular and says there are no trees this big still standing in Toledo District.

I’m appalled. “Are you telling me there’s no high bush left?” High bush is pristine, untouched rainforest—canopy.

He’s emphatic: there is no more high bush in Belize. (He is later proven wrong by another Forum member and a high-resolution Google map.)

The next morning I wake up to hear Don yelling from the bottom of the stairs: “Joan! You have visitors!”

It’s 5:30 a.m. and I am not a morning person. Groggily I climb into my clothes and trudge downstairs. Seated at the head of Don’s table is a stately-looking Maya woman dressed in her Sunday best, her gleaming black hair looped into a figure-eight twist, wearing the heavy, rose-gold earrings that distinguish Maya women from women of any other ethnic group in the country. Forty-two years ago, Maxiana was one of my students. Now she’s a grandmother.

I hug her, the same way I would greet any long-lost friend. Maxiana allows herself to be hugged but doesn’t hug me back—the Maya of her generation seldom even shook hands. I also hug Miriam, her seventeen-year-old daughter, who seems to have had a little more experience with hugs. The four of us sit down for coffee and to talk.

Maxiana remembers some English but says she’s too embarrassed to speak it, so Miriam and Don translate. She has come to formally invite me to visit her house tomorrow, and probably to make sure I’m really here after all these years. She says she and her two married brothers are the only people left of my former students and their families in Santa Elena. Like many Maya communities nowadays, it’s a village of old women and children. A few men still plant corn, but most leave during the week to work on the shrimp farms or at nearby resorts and only come home on weekends.

Before I left the States, I wrote Maxiana in Santa Elena to tell her I was coming. It was a shot in the dark, since Kekchi women, at least the ones in Belize, take their husband’s name when they marry. Miriam, her youngest daughter, wrote back to say her mother often talked about her “Teacher” and was excited to hear I was coming. She also said that her mother had married Esteban Choc—the only reason my letter reached her. Maxiana and her husband had nine children. Three died in infancy, a common-enough occurrence as the Kekchi still prefer to have their children at home. When Miriam was three years old, a fer-de-lance, the deadliest snake in the jungle, bit her father on the foot. He died the same day.

After Maxiana and her daughter leave, Don takes me sight-seeing. He drives from store to store, all of them tiny, picking up fresh eggs at one place, “biscuits” at another, and a locally-made snack of very thin, crisp, sweet tortillas at a third. Two of the stores are owned and run by Kekchi who speak fluent, American-accented English.

When Don and I come back to the house he makes lunch—eggs fried with sliced cherry tomatoes, a traditional Kekchi dish, although they use more chile pepper than he does. Then he makes us each a milkshake. This one is juice-bar quality—fresh grapefruit juice, water with dried milk added (dairy products are still almost non-existent in Toledo District), and a ripe plantain. I have to laugh. Don doesn’t have a telephone or hot water, but he has a blender.

We spend the afternoon reminiscing until the archaeologists come back. Don’s TV only picks up two channels, both from Guatemala. To hear the news in English, he listens to the BBC every morning at six. He blasts me out of bed more than once because he has the volume turned up so high.

The next morning Francisca, who spoke Kekchi before she learned English (she also speaks Kriol—in most Caribbean countries it’s spelled Creole), drives me to Santa Elena to visit Maxiana. When we approach the village we see the ice cream truck—the Belizean Good Humor Man. Francisca asks me to buy her a sour sop ice cream cone. It tastes a lot better than the last ice cream I had in Belize, which was made with sweetened condensed milk.

As I carry the ice cream back, three Kekchi children appear with small woven black and white baskets for sale. The Maya rarely made baskets when I lived here. A few women made clay cooking utensils, but only if they couldn’t afford metal ones.

My first impression of Santa Elena is that it looks like a big lawn dotted with houses. Not only is the bush gone, but so are most of the trees. I was warned by Forum members that Hurricane Iris in 2001 had destroyed most of the tall trees in the area, but that didn’t prepare me for how naked the village looks.

Maxiana sees us drive in and stands outside her house so we know where to park. Nearly all the women wear Western clothing except the recent immigrants from Guatemala, who still wear the traditional long blue skirts and don’t want their pictures taken.

When Francisca and I enter Maxiana’s house, she offers us seats on upturned plastic buckets (they have obviously replaced the wooden bancos of my day) and serves us warm, pre-sweetened coffee. I ask her if she knows what happened to my other students, and she says most of them have moved to San Roman. Maxiana’s older sister, the woman I considered my best friend in Santa Elena (she taught me everything I know about cooking over an open fire), is dead. Maxiana says my house is gone. So is the schoolhouse where I taught.

Then she retires to the kitchen, where she prepares a meal for us. By now we have attracted a horde of Kekchi children who hang around the open doorway to peek at the odd spectacle of a sac li gwink (white woman) and her Kekchi friend (Francisca), who wears shorts and pulls her hair back in a ponytail, but speaks their language as well as they do.

Maxiana’s oldest daughter arrives with her baby. In profile, her face looks exactly like the carvings on the ancient Maya temples.

Finally Maxiana serves lunch, treating me and Francisca the same way her mother would have treated honored guests—by giving us food and watching us eat without eating herself. Maxiana and her family are obviously very poor, and even though the food is simple—freshly-made corn tortillas and eggs scrambled with spicy, store-bought Vienna sausages—I have the uncomfortable feeling that I am literally taking food out of her family’s mouth.

Afterwards I ask Maxiana if I can photograph her kitchen, which more or less resembles the one I used to have except that her fireplace is molded clay and mine was made out of river rocks.

Miriam takes me on a walking tour. Like most Maya villages in Toledo District, Santa Elena still has no running water, electricity, or phone service. But everything else is different. One woman tends a flower garden in her front yard which includes a ginger plant. Half the villagers wear Western clothing. Cats snooze in the open doorways. Clothes dry on wash lines, not spread out over bushes. (No bushes, either.) Miriam says she’d like to go to high school in Punta Gorda, but her mother doesn’t have the money. A high school education is not free in Belize.

I hug Maxiana and Miriam goodbye and promise I’ll see them again—I just don’t know when. This time Maxiana hugs me back.

Francisca and I stop at the Rio Blanco Falls to cool off. It’s now a National Park, but the rain has been so sparse in recent years that the falls have been reduced to a trickle. When I lived here, the women bathed in the pool at the bottom of the falls and washed their clothes downstream.

I ask Don about driving to San Roman, but he’s not enthusiastic. Once I discover how much gas costs—about double what I pay in the States—I give up on the idea.

The rains start that night—June is the beginning of rainy season. The electricity goes off while I’m using the bathroom downstairs, and in my haste to reach the flashlight I knock it off the chair and then can’t find it. The house is as dark as the inside of a pocket, and I have to feel my way along the wall to the staircase and up to my room. I keep thinking about the coral snake Don killed inside the house about a month ago.

After breakfast he drives me to his farm, which he planted in orange trees. But he’s leasing it to a Kekchi family because “I’m too old to be climbing ladders to pick oranges.” He built the house where I’m staying now after Hurricane Iris, which left his grove intact but destroyed his home and the old base camp.

As we snack on Surinam cherries—they’re tart and Don says they make good jam (he put up the orange marmalade I’ve been eating on my breakfast toast)—I photograph a Cortes tree. The Kekchi still use this wood to frame their houses. The tree is so tall I have to photograph it in segments. Don says it’s a testimonial to the tree’s strength that it’s still standing—Hurricane Iris packed winds up to 140 mph.

After lunch I do laundry in Don’s toy-sized Guatemalan-made washing machine and hang my clothes outside to dry. By the time I take them down they’re stiff as potato chips.

Since it’s Sunday and the archaeologists aren’t doing anything, we all pile into two cars and drive to see Nim Li Punit, an ancient Maya site nearby. The ruin isn’t extensive, but it’s been beautifully reconstructed and maintained. Nobody knows what the ancient Maya called it. Nim Li Punit is Kekchi for “Big Hat,” because one of the stelae shows a ruler wearing an elaborate headdress.

The next day Don drives us to the archaeologists’ site. It rained again last night, and the site is muddy and thick with hungry sand flies. At last—two more things that haven’t changed: mud and hungry sand flies.

It’s just past noon, not a particularly good time to take photographs. The linguist in the group splashes water on a few of the stelae to bring out the details. Standing next to him, I get goosebumps as he scans a series of glyphs (syllables of speech in pictorial form) and translates them: “This site was built in [the date] and commissioned by [the name of the ruler].” The team has found two tombs so far, both looted, but they’re confident that once they start exploring, they’ll find more. (They do.) The bush is still pretty formidable, even though it’s second growth. Two days later they kill an eight-foot fer-de-lance.

Francisca and I go to Placencia the next day because she wants me to meet her oldest son, who works at one of the hotels. We travel the way Belizean locals do—catch the bus on the highway (they play American country music), get off at Mango Creek, and take the motor skiff across the channel. It’s a cool, overcast morning, threatening rain, and a beautiful ride.

Placencia is primarily a tourist town, very pretty and slow-paced. At the hotel—which is owned by Francis Ford Coppola—I meet Francisca’s son Ralph. His boss, the manager, comps our lunch. The food is good and the grounds are beautiful. They ought to be, with rooms costing upwards of $1,000 a night U.S.

On our return trip the bus isn’t air conditioned, so everybody has the windows open. Belizeans let you board their busses and boats and don’t ask you to pay until you’re halfway to your destination.

That night I tell Francisca I want to take her, her husband, and their two youngest boys out to dinner so she won’t have to cook—she’s done so much running around on my behalf that I’ve filled Don’s truck up with gas three times. (Her oldest son lives at the resort, and the next oldest is at a boarding school in Belize City.) She chooses Coleman’s, a local place right off the highway. It’s family-run, and the owners, a young Kriol couple, live behind the restaurant.

As we enter, the husband points out a line of army ants swarming around the foundation. He wants to spray them with poison, but he doesn’t want to do it while we eat. (In the bush, these ants travel in swarms like an invading army, and can strip the meat from your bones in a matter of minutes if you’re unlucky enough to be in their way.) But he’s obviously afraid they’ll get into his house—I would be too. Halfway through dinner the scent of insecticide floats in on the evening breeze.

Tonight’s special is fresh grouper, served with coleslaw and more fries than I can eat. The wife, who’s the cook, comes out and questions Francisca. Is there something wrong with her fries? Why haven’t I eaten mine? Francisca explains that there’s nothing wrong with her fries—I ate a big lunch in Placencia. The couple’s two kids go to school with Francisca’s, and all four ignore the grouper and the fries. Who wants food? Cable television has arrived! While the rest of us eat, the kids sit mesmerized, staring at a kung fu movie with subtitles.

Don still does a little farming—green beans, tomatoes, a few other vegetables. The next morning he heads for the bush with his dogs, where he tracks leaf-cutter ants—known locally as wee-wee ants—back to their nest so he can destroy it before the ants destroy his garden. He wears black rubber boots, which the Maya men still wear whenever they work in the bush to deflect snakebite, and carries his machete barehanded. No leather sheath.

After lunch we sit around and talk, since this is my last full day in Belize. Don tells me the noisy birds in the bush that shriek and chatter every morning are chachalacas. But he mainly wants to talk about the Kekchi. When outsiders, even anthropologists, talk about the “modern Maya,” they’re primarily interested in “educating” them away from their traditional practice of slash and burn agriculture because it kills the high bush. Other professionals speculate that today’s “high bush” is not first-growth rainforest. The ancient Maya themselves destroyed it for firewood and to clear land for their crops.

But Don’s main concern, since his entire family is Kekchi or part Kekchi, is the Maya people themselves. It’s a question I never thought to ask when I lived here, but what do you do with an indigenous people whose culture is so at odds with the culture of the dominant society? Do you encourage them to remain quaint curiosities, like the native Americans in the United States, or to assimilate and become part of the Belizean melting pot? And how can they make that choice if there’s a price tag on education?

Don and Francisca drive me to PG the following morning so I can catch the 10 a.m. flight back to Belize City. I’m sad to leave because I don’t know when I’ll see them again, and I wish there were some way I could make sure Miriam goes to high school. But mostly I’m sad because I waited forty-two years to come back.

©2005 by Joan FryAll rights reserved